In recent years, the debate over the minimum wage has gained renewed relevance. This blog has extensively discussed the role of the minimum wage (here, here, here, or here), its effects on employment, and inequality (here and here), but much less has been discussed about the channel that is fundamental to understanding its impact on well-being: household consumption. In this post, we summarize the results of our work on the impact of the increase in the interprofessional minimum wage (SMI) in Spain in 2019 on consumption (you can access the full article here).

Understanding this channel is key to assessing the well-being of lower-income households. For example, a slight increase in consumption (perhaps due to savings) is not the same as a significant increase in consumption, nor is it the same whether consumption of basic necessities is increased or whether the consumption basket includes non-essential goods. Furthermore, from the perspective of local economies, wage policies can generate multiplier effects in the economy through demand, especially in countries like Spain, where a significant portion of employment is concentrated at low wage levels. Despite its potential relevance, there is still relatively little evidence on the influence of wages on consumption, especially outside the Anglo-Saxon world, mainly due to the lack of public data that allow for rigorous analysis.

Our work focuses on the 2019 reform of the minimum wage (SMI), which led to a 22.3% increase in the minimum wage, the largest in four decades. To measure its impact on consumption, we use a novel database with information on millions of anonymized transactions made with bank cards and point-of-sale (POS) terminals from a major financial institution, aggregated at the municipal level, with a weekly frequency, and for different consumption categories. Our data cover the period from January 2018 to December 2019.

One of the main empirical challenges of the analysis is that the reform was implemented simultaneously throughout the country, which makes it impossible to identify its effect by comparing affected and unaffected regions, as has traditionally been done in the literature on minimum wage and employment. To overcome this obstacle, we exploited the geographic variation in exposure to the reform, defined as the percentage of working-age individuals in each municipality whose income in 2018 was below the new 2019 minimum wage. This information comes from the sample of 2018 personal income tax returns provided by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, which allows us to construct a granular measure and include almost 2,000 municipalities in the analysis. These municipalities represent 78% of the total population.

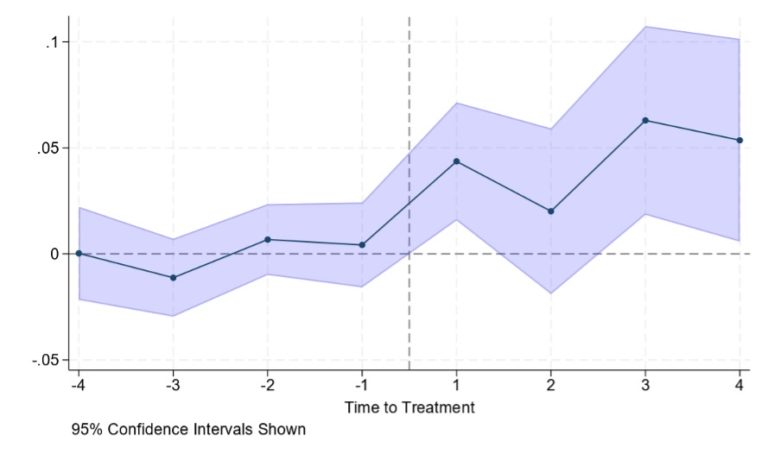

Using this exposure measure, we compare the evolution of consumption between more and less exposed municipalities, before and after the reform. Figure 1 shows the results of the event study, adding coefficients by quarter for 2018 and 2019. Before the reform came into effect, consumption followed similar trajectories in both groups of municipalities. However, after its implementation, the most exposed municipalities experienced an average increase in consumption of 4.5% relative to the least exposed. This increase is observed in the first quarter after the reform and persists throughout 2019. These results are robust to alternative specifications and various exposure measures.

Figure 1. Effect of the increase in the SMI on per capita consumption at the municipal level (2018-2019)

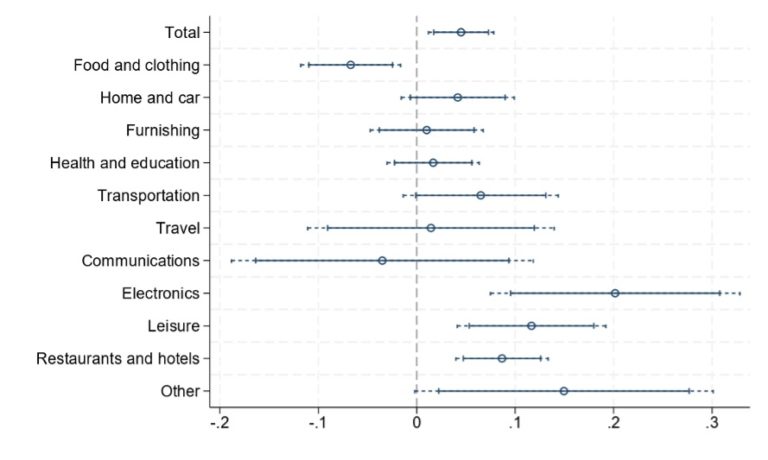

When disaggregated by expenditure type, we observe that the increase was concentrated in discretionary goods categories: electronics, leisure, and restaurants and hotels. In contrast, a negative effect was observed in food and clothing, which could indicate some degree of substitution between our categories of essential and non-essential goods. In contrast, no significant changes were detected in other expenditures such as furniture, education and healthcare, or travel (Figure 2). This pattern suggests that households affected by the reform were already able to cover their basic needs and used the additional income to improve their well-being through non-essential consumption.

To validate these results, we used individual data from the Household Budget Survey and conducted a difference-in-differences analysis. We found that households with low-income primary breadwinners in 2018 increased their consumption by 4.6% in 2019, showing similar patterns in expenditure composition to those observed in the exercise with banking data. Furthermore, a placebo test in the previous year did not detect differential effects, reinforcing a causal interpretation of our results.

Figure 2. Effect of the increase in the SMI on the composition of consumption

To complete the analysis, given the close link between consumption and employment, we applied the original empirical strategy to evaluate labor market effects. Our objective here is to determine the extent to which the impact on local consumption is the result of a net effect between income increases and potential job losses. To do so, we used data on registered unemployment and contract creation. We found no significant differences between municipalities with high or low exposure, either before or after the reform, indicating that the measure did not significantly affect the labor market when we consider its effects at the local level. We also observed no significant differences in the results between nominal consumption and inflation-adjusted consumption, suggesting that the reform did not significantly affect prices during the period analyzed. However, this hypothesis requires more detailed investigation in the future, with special attention to those productive sectors most exposed on the supply side.

The consumption results are consistent with economic models with non-homothetic preferences, in which households prioritize meeting a minimum level of consumption of basic goods and allocate additional income to more elastic goods, such as leisure or electronics. In this sense, the 2019 minimum wage reform not only improved the purchasing power of lower-income households but also expanded their access to forms of consumption associated with a better quality of life.

In short, the minimum wage can be an effective tool for improving households’ material well-being, not only by raising consumption levels but also by changing their composition. At least, this is what our results suggest in the specific context of the 2019 reform.